Home » Interviews » Khaled Al-Hajar: Politicisation of International Film Festivals Requires us to have Self-Confidence and Produce Films that Reflect our Issues and Communities

Interviews

Khaled Al-Hajar: Politicisation of International Film Festivals Requires us to have Self-Confidence and Produce Films that Reflect our Issues and Communities

Published

11 months agoon

By

Huda

Khaled Al-Hajar to Arabisk London: Politicisation of International Film Festivals Requires us to have Self-Confidence and Produce Films that Reflect our Issues and Communities.

Interviewed by: Mohsen Hassan

Despite receiving a Master’s degree in directing and writing from the National Film College in London, his long-held obsession with achieving professionalism and specialisation in film directing has led to numerous awards for his diverse and distinguished works locally, regionally, and internationally.

He still feels, nonetheless, a tremendous deal of gratitude and pride for that early time in his life, which connected him with the renowned Egyptian and international filmmaker, Youssef Chahine.

During this period, his personality, directions, and methods for interacting with the arts and inventions of the Seventh Art began to take shape. These lines became more defined, profound, and long-lasting.

Khaled Al-Hajar, an Egyptian director, affirms in the interview with Arabisk London that cinema is a tool for expressing reality and raising individual and societal issues.

He attributes his vision to his membership in the Shaheen Film School and his early experiences as an assistant director, which he believes contribute to his ability to create a comprehensive message and deep reality expression.

Al-Hajar discussed a wide range of topics during the conversation, including the state of Arab cinema, its prospects in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, his work in the UK, and the potential for collaboration on productions between Riyadh and Cairo.

He also shared his predictions and evaluations regarding the characteristics of both local and foreign cinema as well as the Red Sea Film Festival in the upcoming ten years.

Firstly, when did you start working as an assistant director for the late great Youssef Chahine?

I worked with Youssef Chahine when I was twenty-one years old and in my first year of law school, as part of my training for the film Goodbye Bonaparte, which premiered in 1985.

Subsequently, I collaborated with him as an assistant director on two films: The Sixth Day and Alexandra Again and Again. Shaheen also produced my debut short film, “You Are My Life,” which starred Abla Kamel and Ahmed Kamal and produced in association with the Goethe Institute.

Then, regarding the 1967 setback, he produced my first feature picture, Small Dreams. Filming took place in the Governorate of Suez and features Salah Al-Saadani and Mervat Amin. The production is German/Egyptian.

What characteristics of the enduring creative influence did this Shaheen Film School experience leave behind?

I am among the many individuals who have graduated from the Shaheen Film School. It makes you more likeable to films and forces you to approach your skills with obligation and gratitude.

This filmmaking school also emphasises freedom and well-chosen topics, moving away from mere visual spectacle, so that the films carry an analysis of significant social issues. I applied this to films like “Longing” and “Forbidden Body.” Youssef Chahine’s cinema also teaches you to bring happiness to the viewer through your choices and themes. Examples of this include ” Girls’ Love” and “There Is No Other Than This,” which feature singing or romantic comedy. In general, Shaheen taught me the love and devotion to film.

Additionally, he taught me to remain focused and not give up or give in to the harshness of the circumstances and surroundings, and to see it as a message rather than a business venture.

Because of this, I owe him credit for my presence in the film industry. In recognition of his impact on both my career and the development of my generation of great directors, I dedicated the Best Direction Award I received at the Cairo Film Festival to his soul.

What remains steadfast and evolving in your beliefs as a filmmaker after numerous participation in international film festivals?

After all these years of participation, I still firmly believe that the major international film festivals—Venice, Cannes, Berlin, Rotterdam, and so on—are politicising events with exhibits that frequently reflect trends.

This implies that you and your films—which may include films from Eastern Europe, Syria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Palestine, and so on—will be the talk of these festivals if there is a war or other calamity in your nation.

I should not, therefore, as a director, tailor my films to specific festivals. Instead, I believe that my films ought to have a national and local audience repertory; in other words, they ought to prioritise the needs of their audience before those of the festivals.

Local public is the foundation and is the most long-lasting, whereas festivals are urgent and transient. My film’s recent distribution serves as evidence of this, Girls’ Love, in Egyptian theatres and on electronic platforms, among other places, although it was produced and directed two decades ago. During the filming process, I was eager to address a topic that affected my community rather than the festival community.

Does this imply that you have no interest in winning major international awards?

On the contrary, every director hopes that his films will win both domestic and foreign accolades. It is a positive thing for the director to receive recognition for his work, but it shouldn’t come at the expense of the cinematographer’s high standards of performance.

It is a well-known fact that even worldwide directors are aware that works that earn politicised accolades do not necessarily reflect the calibre of the work, its capacity to endure, or its unique appeal to the general public. Thus, they don’t make art to win, especially at festivals, but rather to speak to their people first.

Therefore, we must have faith in our abilities and focus on producing cinema that speaks to our people and our innermost feelings. By doing this, we will compel film festivals worldwide to adjust to the unique concepts, pieces, and problems that we bring. It is a catastrophe if you produce a movie that only the festival audience sees and not the citizens of your nation!

How much do you think the output of Arab film has achieved in terms of quantity of production and depth of coverage of shared national themes?

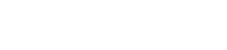

The finance and trends in the film industry determine how things are going to evolve in the Arab cinema industry. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s recent involvement in the direct and explicit creation of several cinematic films is fresh. Making the Saudi film “Shehana” has given me more chances to showcase well-funded films.

Even though the films that are currently being shown are of lower quality than the older ones, I hope that a large number of works and the introduction of fresh writers, directors, and filmmakers will restore things to normal and prevent the works from becoming like American films, which are visually stunning but lacking in substance.

It’s worth noting that this is a skill that only Americans possess, so things will undoubtedly get better the more authentic you become and the more you stay away from copying American films. I generally enjoy seeing professionally produced films from Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Jordan, Egypt, the Emirates, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, no matter how big or small.

In the upcoming years, I anticipate that the rate of exaggeration at both production and industry levels will decrease in a manner that will stabilise real cinematic standards and drive out other factors and perspectives that are exclusive to the business.

Do you think that successful businesses and industries always result from massive film funding?

While there are large financial funds currently circulating in Arab cinema, I believe that not all cases will benefit from this kind of funding, particularly if the incubating environment for cinema is still in its infancy and first launch, huge funding does not always translate into good results at the industry level and the works presented.

As a result, before allocating large sums of money, certain matters must be resolved, such as training and educating a youthful, enthusiastic audience for local cinema. This is precisely what the Arab world needs, considering that most young people are drawn to European and American films, except Egypt, which has had local cinema audiences for more than a century.

Cinema without viewers becomes just television, therefore the Arab public, which has become accustomed to Egyptian cinema, now needs to adapt to Saudi, Tunisian, and other cinema.

As a filmmaker, what does the UK stand for? Are there any upcoming art initiatives in any cities in Britain?

My second nation is Britain. I’m dual-national, British and Egyptian, and I’ve spent the last 35 years living in London. Janice Rider, my wife, is a visual artist and clothing designer, and Adam Al-Hajar, my son, is an actor in London. For nearly twenty years now, I have been living alternately in Cairo and London.

I received a master’s degree in directing from the National Film College in the United Kingdom, where I also earned a great deal of experience in the filmmaking industry. In addition to teaching and occasionally giving lectures about directing and movies, I have ongoing projects in the United Kingdom and strong friendships with artists in London and throughout Britain.

In reference to your friends who are British artists, why do you think your luck in film directing is better than theirs?

Because unlike me, they were unable to direct a large number of cinematic works. Compared to the English directors, I was more fortunate because I attended the same college as them. For very little money, I directed ten feature films and four big series, each with thirty episodes.

There, I directed the production of Room to Rent, a big film financed in 2000 with five million pounds sterling from the French Canal+ and the English Channel 4. It starred several actors, including Rupert Graves, Saïd Taghmaoui, Flaminia Cinque, and Clémentine Célarié.

The film was distributed to over 25 countries worldwide and screened in England and France. It was the film that took home the most audience awards at festivals and gained other accolades. As the first movie I directed after graduating and the first Arab director to helm both an English and a French feature in the same country, I was fortunate. since both countries collaborated on the film’s production.

How do you see Saudi Arabia’s attitude towards the film industry today? When can we say that the Saudi film industry exists in terms of identity and nationality?

The film industry in Saudi Arabia and the Arab world at large will be greatly impacted by this very positive openness. The demand for Saudi films was evident during my stay there, as demonstrated by the 2019 release of Shehana, and is one of the factors that is currently fostering the emergence of a new generation of national filmmakers in Saudi Arabia.

The film made a lot of money and stayed in theatres for a long time because the Saudi public demanded to see it because it tackles the topic of terrorism and society, even though the story, which is based on a true incident, depicts the tragedy of a Saudi girl who was abducted from her mother and taken to ISIS in Syria along with her brother.

As a result, I can now categorically state that Saudi film exists and has a distinct character, and I anticipate that this industry will mature significantly over the next several years.

How much of a creative, commercial, and soft power role do you think the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia can have in the film industry?

Saudi Arabia is, of course, able to do that to a considerable degree, and this is typically related to the calibre of films that are shown in cinemas. It is no secret that films may depict and address a wide range of subjects and concerns, including, for example, terrorism and extremism.

Given how much of an impact films have on people’s lives, the Kingdom will always have the chance to use films as a creative, commercial, and soft power.

A few films in Egypt changed some legislation. Two films that had a significant impact on the legislation were: They Made Me a Criminal (Farid Shawqi) and I Want a Solution (Fateen Hamama). The films altered the penalties for juvenile offenders in theft cases and legislation about women and divorce respectively. However, the Kingdom is fully aware that films have a significant impact as a soft force in shifting the perception of the industrialised nation among other countries.

For instance, American films consistently portray the US as a successful nation that its adversaries are hostile towards. Films have frequently been utilised in America to portray people as lovers of family, life, and hope.

This applies to political ideas as well. In my opinion, we will be better than the Americans in addressing our issues through cinema, away from American cultural deception for the people. All of these ideas and values are placed within American films to achieve their goal, even though it’s possible that they do not exist in reality in their lives. Saudi Arabia will undoubtedly be successful in using films to convey powerful messages on all fronts.

Where, in your opinion, should Saudi Arabia’s film industry begin to flourish? Which is more significant, long or short films?

First of all, I have seen a great deal of growth in Saudi cinema and films, and both kinds are deserving of attention in my opinion. The important thing is to consider deep cinematic standards in terms of writing, handling, directing, acting performance, and other aspects, rather than just the length of the film. What matters for me in this case is that the film industry has truly taken off in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

It has progressed through several stages of modernization and development; all that is left is to carry on with the same strategy, impulsively and passionately, to ensure that the issue is not merely a boom and finish. In actuality, for the momentum of cinematic productions to continue, there needs to be consecutive Saudi film seasons and events all year long.

For instance, the Ramadan season, Little Eid, Great Eid, and numerous other holidays in Egypt inspire filmmakers to present a wide range of themes and films. They also encourage the audience to be enthusiastic, anticipatory, and ready for each new release, which is something I hope to see in the Kingdom as well.

According to some, Egypt and the Kingdom are open to working together on films. Is this a viewpoint you share? How might one go about implementing collaboration?

Saudi Arabia is one of the major backers of the Egyptian film industry; for many years, MBC and ART, among other Saudi channels, have been showing Egyptian films. Sheikh Saleh Kamel, may God have mercy on him, produced my film There Is No Other Than This. 2019 saw the release of my movie Shehana. Albert Haddad, a Jordanian, serves as executive producer, and it is produced by Saudi TV and Mr. Daoud Al-Sharyan. When it debuted in 2000, it was a huge hit.

Starring Saudi performers, it ranked second on the Shahid platform in 2001 for the most views. This movie is a part of the cinematic collaboration between Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. There are ongoing initiatives, and the field is ready and available for significant collaboration between Saudi Arabia and Egypt in terms of directors, performers, and various work crews.

To forge a sophisticated cinematic alliance between the two nations, it will enable the production of multiple collaborative films. This is a healthy and natural development that will benefit Cairo and Riyadh in the long run.

How do you envision the future 10 years of Saudi film output and content quality, from a cinematic perspective?

The goal of any cinematic openness, like the one the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is currently experiencing, is to advance the industry as a whole, including its human and technological constituents.

And so that this openness grows to produce bigger, better, and more truthful films that may address regional concerns and issues, actively participate in festivals, and win significant and prestigious awards. Moreover, the film industry has had a great deal of backing and money from the Kingdom, indicating that this is something that the sector is concentrating on accomplishing to make it successful and localise it.

How would you rate the Red Sea International Film Festival? What can this festival bring to rival Hollywood and other events?

The Red Sea Festival holds considerable creative significance throughout the Arab and worldwide film communities. Having attended its programmes twice, I found that the selection committee had made excellent decisions about the standard of the films and the subjects shown. This festival greatly influences the growth of Saudi Arabia’s film industry and content.

I anticipate a significant boom in this festival’s content, activities, and upcoming cinematic projects, which is necessary given the diverse presence of well-known actors and filmmakers worldwide and the significant Saudi spending the Kingdom is seeing to support cinema and spread its culture among Saudis.

In my opinion, this festival lacks nothing but continuity because it provides a crucial basis for the growth of the cinematic movement and its constituent parts. When it comes to momentum, strength, presence, and level, it never falls short of any international festival.

It will only develop and gain depth and history throughout the years and sessions if there is continuity. This festival will undoubtedly give rise to promising Saudi generations, and Saudis will experience a sense of nostalgic cinema due to its events, recurrence, and succession.

In conclusion, why do you prefer to be in Cairo right now? What is new in your film-directing endeavours? Will Saudi theatres ever get the chance to showcase one of your works again?

I would rather travel to Egypt at this time because it is more difficult to secure consistent funding for films in England.

God willing, the new project will debut after Ramadan and feature Elham Shaheen, Ahmed Fathi, Houria Farghali, and other notable actors. Under the title “All Love,” with any luck, Saudi Arabia will show it with “Shehana.” In addition, I am working on a series that I am excited to present, called “People of Love.” Elham Shaheen is also in it, and naturally, the film will take precedence. Following Eid al-Fitr, filming is going to begin.

You may read about Arabisk London Interviews Percussionist Mohamad Shahada: A Magnificent Musical Scientist from Damascus to the Rest of the Globe

Nammos Resort AMAALA: KSA’s New Address for International Luxury Hospitality

Muhammad Mahfouz: Trump will Respond to Riyadh’s Ambitions, and We Must Develop a Gulf-Arab Project with Iran

The World Stadiums & Arenas Summit 2025 has Arabisk London – Saudi Arabia as a Media Partner

Laheq: The First Private Saudi Island to Obtain Light at Last

The “New Square” Alters the Modern Life’s Notion in Riyadh