Home » Saudi Arabia » Princess Reem Al Faisal to Arabisk London: Arab Art Mimics Western Art and that Art Should be Redefined to Fit Our Culture

Interviews

Princess Reem Al Faisal to Arabisk London: Arab Art Mimics Western Art and that Art Should be Redefined to Fit Our Culture

Published

3 months agoon

By

Huda

Some people are born in a specific location and live there, whereas others seek to discover new cultures and beauty through literature, art, music, or painting. Some use the camera lens to travel to other worlds, while others use art, music, or painting to bridge the gap between nations and people. Saudi documentary photographer Reem Al Faisal exemplifies this idea. These individuals bridge nations and peoples by capturing and preserving beauty.

Interviewed by: Mai AbdulLatif Suleiman

When Saudi Princess Reem Al Faisal decided to become a professional photographer at the age of sixteen in Jeddah, she embarked on a thirty-year journey filled with successes and setbacks.

Following graduation from King Abdulaziz University with a Bachelor of Arts in Arabic Literature, she enrolled at the Speus Institute in Paris to study photography. She then set out on a journey through the world’s civilisations with her camera lens, which managed to carve out a niche for itself that is challenging to duplicate or even copy.

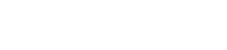

In 1998, she debuted professionally in Jeddah with a series of black-and-white photographs of Paris. She then displayed her work at the Jeddah Islamic Port, where she was the first Saudi photographer to capture its intricacies. She was also the first photographer to capture the specifics of the Hajj ceremonies at Mina, Mount Arafat, Muzdalifah, the location of the Jamarat, and the Grand Mosque in a way that was distinctive and able to capture Islamic culture as a legacy that is beautiful to everyone, no matter where they are.

Reem Al Faisal’s photographs of the Creator’s creativity and human life that longs for immortality in all its details have been shown in several exhibitions. Her work has documented everyday life and landscapes in various countries, including America, Iran, China, Japan, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, and Syria.

She was instrumental in establishing a branch of the Speus Institute of Photography in Dubai and established the first photography-focused gallery in Dubai, the Empty Quarter Gallery, in 2009.

Arabisk London discussed this journey, which was full of successes and setbacks, with Saudi documentary photographer Reem Al Faisal to find out more about its specifics.

What is the reasoning behind your lens’s ability to confine itself to black and white? Occasionally, the artist thinks that the wide range of colours in his hands is insufficient to express his notion.

I think that black and white, photography has a unique symbolism that may express the image’s philosophical and metaphysical elements. Because it enables the photographer to detach from reality and portray its hidden meanings, this style of photography was and is seen by my generation as more professional.

At what point did Princess Reem Al Faisal start using colour photography? Do you think that taking this action was a bit late?

I tried taking pictures in black and white when I first started taking pictures of big areas in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia about four years ago, however, I didn’t think that these two colours were sufficient to express what I wanted, so I started using digital photography for the first time. This was the point at which I started taking pictures in colour.

Initially, I was keen on taking pictures of the paranormal and people interacting with their environment. However, when I began using colour photography, the subject matter changed to colour, so I don’t think I was late in making this move because it didn’t align with my initial objectives.

What impact did your international trips have on your development of artistic vision?

I see photography as a form of travel, using the camera to investigate civilisations, cultures, and national histories. I always prefer to put myself in the shoes of the subject I’m photographing, viewing the scene through the eyes of an outsider, allowing the location to tell its own story and express itself separately from my own.

Do you believe your photographs have eradicated the disparities between civilisations and cultures?

My photographic style has always varied from place to country, reflecting the essence of each nation and its civilisation. I strive to absorb the culture of each location so that it is represented in the photographs I capture. Photography does not eradicate these disparities but rather exposes them as a valuable component of civilisational variety and integration.

Is there anywhere that Reem Al Faisal wishes she could shoot more than once?

I adored China, and its civilisation is extremely similar to ours in Saudi Arabia, I intend to shoot it again if circumstances allow.

Saudi Arabia is now experiencing a significant artistic revival. What do you see as missing from this movement, despite its tremendous progress?

I see that the Arab artistic movement as a whole still needs several things, the most crucial of which is trust in our civilisation. I can realise that current Arab art is only a copy of Western art and culture.

Even the highest value of current arts in the Arab world does not stem from our civilisation, which is old and highly rich in all aspects, and to which no culture in the world owes anything in language, writing, and religion. Despite its wealth, Arab art in the contemporary period has been unable to replicate this true civilisation.

So, do you think Arab people have become more consumers than producers?

Yes, and this isn’t new. We’ve become a consumer culture since colonisation weighed us down. Although we are a culture famous for its rebirth, I have yet to witness this rejuvenation. All I see are imitations of other civilisations.

What suggestions do you have for recovering this renewal?

I believe that the problem rests with academic institutions in terms of redefining Arab art in a way congruent with our culture rather than other civilisations. Modern Arab art, for example, believes theatre to be the beginning of the arts since it was for the Greeks, but this is not true for us because each civilisation has its features, and there is no first or second-class civilisation. Instead, the issue is complementary rather than competing.

Some argue that Arab civilisation is inward-looking and incapable of integrating with other civilisations, particularly Western ones. Do you agree with this viewpoint?

Arab civilisation has never been closed in on itself; instead, it is the most open civilisation in the world. It is the foundation of all civilisations and the origin of celestial faiths. On the contrary, the West is inward-looking and only accepts what like it. It has even divorced religion from art and culture, whereas, in the Arab world, religion and culture are inextricably interwoven.

If people think our culture is weak because it is related to religion, that is their issue, not ours. Religion was, is, and will always be the wellspring of Arab culture, which separates us from other civilisations.

What are your thoughts on secularism?

What exactly is the concept of secularism? Do we truly comprehend the definition of secularism? Or did we import this phrase from the West? Some argue that secularism is anti-religious, but the fact is that the West developed secularism to tolerate the other.

Before this word was coined, the West was embroiled in deadly religious warfare, but Arabs had lived together for thousands of years amid unequalled religious and cultural variety. Everyone must understand that we Arabs live and use secularism instinctively, to the point where we develop it in its proper sense and do not pretend to apply it in the same way as others.

Do you believe Saudi women were missing from the cultural scene?

For a time, Saudi women were absent from the cultural scene for a variety of reasons, the most important of which was the extremist awakening movement that emerged following the Iranian revolution and the attack on Mecca, however, Saudi women have overcome this stage and have become a founding member of the Saudi state, particularly in the field of development.

Despite the restrictions, women gravitated to study, and there were female physicians, engineers, teachers, and scientists in various areas who attempted to show their presence from their respective positions.

How do you envisage the future of Saudi women in the next stage?

I regard it as extremely affluent since what Saudi women have accomplished in the past is the best proof that they are capable of doing even more, now that all sectors are available to them to contribute to the creation and development of society.

If we gave Reem Al-Faisal the option of living at a different point in Saudi Arabia’s history than the present, which would she choose: the past or the future?

I unquestionably choose the early stage of Islam, the days of the Noble Messenger, peace and blessings be upon him, because I believe that the Arab Islamic culture produced during that period was distinct and had its character from the rest of the civilisations, in terms of production momentum and quality, and that it laid the groundwork for the civilisations that followed.

What stage have the attempts to publish the book Saudi Flashes reached?

I’m currently working on Conditions of Light, and once I complete it, I’ll go on to the book Saudi Flashes, which I believe will take between one and two years to complete and publish.

How do Reem Al-Faisal’s works from her debut exhibition in the 1990s differ from those she produces today?

In contrast to my early black-and-white photographs, which let the setting speak for itself without any personal embellishments, my current photographs are more expressive of my viewpoint. One may interpret the images I took of Saudi Arabia today as a dialogue between my country and myself.

The most recent event that the Arab nations are going through is Syria’s return to independence. What would Reem Al-Faisal’s lens be focused on if she were in Syria right now?

One of my favourite nations is Syria. I have been there before and have taken photos of Palmyra, Sweida, and Damascus. The conflict kept me from returning to finish my photographic expedition. Even though I think Syria is one of the most stunning Arab nations, I’m not sure where to begin taking photos if I were in Damascus.

This nation has many scars, but I see them as positive wounds that will help build a wonderful country. Throughout their history, the Levantine people have endured several instances of injustice, yet they have managed to overcome it and return with all their cultural and intellectual riches.

Which do you think will be more effective in the future at spreading civilizations—the word or the image?

All art comes from words, and even the computer language originates from words!

In your opinion, what part does contemporary technology play in photography advancement, and should we impose any restrictions on its use?

I am among the first Arab photographers to embrace NFT technology since every stage has a unique method of showcasing the arts. Moreover, I don’t think technology will make photography lose its character because that identity is connected to the photographer and not the equipment he employs.

How does Saudi art fit within the Kingdom’s Vision 2030, in your opinion, Princess Reem Al Faisal?

As the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia works to advance the artistic movement, I anticipate that it will have an appropriate bright future. Saudi art is moving forward confidently, accumulating accomplishments to create its own space. I do not believe that art achieves qualitative leaps, but rather that the topic is a result of incremental efforts performed throughout time.

A parting remark for Saudi Arabia’s upcoming generation of photographers and artists?

Whether the photographer’s equipment is state-of-the-art or archaic, it shouldn’t matter. It doesn’t matter. The key question is whether the photographer is wealthy and culturally aware enough to portray this in their images.

To do this, one must read, study, learn, and acquire a great deal of knowledge. It is a compilation of build-ups from science, culture, and civilisation created in a matter of seconds and takes the shape of an image.

The Avenues Riyadh: From Shopping to Lavish Lodging

What Economic Impact Will the 2034 World Cup Have?

Does the Peace Agreement in Ukraine Clash with KSA’s Oil & Economic Interests?

Nora AlShaikh, the Saudi Entrepreneur

Rashed Sharif is Spearheading KSA’s Major Investment Transactions