Home » Saudi Arabia » Dr. Hassan Al-Nemi: Politicians’ Choices Have Power, and so Do the Words of Intellectuals!

Interviews

Dr. Hassan Al-Nemi: Politicians’ Choices Have Power, and so Do the Words of Intellectuals!

Published

4 weeks agoon

By

Huda Az

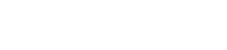

Dr. Hassan Al-Nemi, a Saudi critic and writer of short stories, is heavily involved in the literary, artistic, and cultural life of the Kingdom, the Gulf, and the Arab world. To reach the recipient’s tastes and world, he consistently uses contemporary media technologies in his literary, cultural, and artistic presence.

Interview by Mohsen Hassan

Consequently, he is currently occupied with rectifying numerous conceptual deviations and ambiguities in philosophy, literature, and thought through his personal TikTok channel.

During his interview with Arabisk London, Dr. Hassan Al-Nemi discussed several primary concerns and topics related to the Saudi critical experience. In addition, he addressed the conflict between literary genres, liberalism, its concept and existence in the Arab and Gulf worlds, the schizophrenic nature of the intellectual-politician relationship, the essence of literary and artistic creativity, and the contemporary factors that determine men and women and how, among other themes, dimensions.

He also discussed the creative woman‘s obsession with writing about men, which may lead to realistic descriptions that are distant from the problems and aesthetics of literature and its deeper inspirations.

To begin, how do you see Saudi literature’s present and future in the context of recent and ongoing cultural changes?

The publication of the book “Explicit Thoughts” by the poet and critic Muhammad Hasan Awad in 1926 marked the beginning of the critical experience in Saudi Arabia. Although this essential book focused more on critiquing phenomena than texts, it did raise awareness of the significance of addressing the concepts that make up the overall context. It was critical of the conservative phenomenon that subtly ran counter to the concept of the modern state.

The initial spark that ignited my critical thinking was this book. Later generations were impacted by the concept and connected it to its Arab counterparts, particularly Dr. Taha Hussein’s ideas, even though its impact on the local critical experience waned.

Different generations have had various experiences with Saudi criticism. One example is Ahmed Al-Sibai, who was Al-Awad’s contemporary but approached the subject from a different perspective. In addition to writing reformist novels, such as “Fikra,” he debuted his first theatrical production, though it was not staged for social reasons at the time.

This is all the result of a new consciousness. Al-Ghadami, Al-Suraihi, Al-Bazie, Moajab Al-Zahrani, and others’ experiences might be a continuation of this first critical trend. Later critical experiences—both phenomenological and textual—have broadened the perspective and made a substantial contribution to Arab criticism.

Has the Saudi literary criticism system succeeded in establishing a path towards professionalism and excellence, in your opinion?

Indeed, excellence. From Dr. Abdullah Al-Ghadami’s experiences in textual criticism to his most recent contributions in the field of cultural criticism, the most esteemed Arab universities study his books, regardless of whether we agree with him or not.

Regarding professionalism, if the goal is to commodify criticism, I don’t think any Arab critic has succeeded in turning criticism into a career. In actuality, literature as a whole—its texts and criticism—is merely an entirely subjective endeavour.

To what degree does Hassan Al-Nemi think that literary genres clash? And why is the tension between poetry and the novel so prevalent in the Arab literary scene?

Critics and observers are on opposing sides of the conflict, which does not start within literary genres. Texts naturally overlap, and in my opinion, this is more in line with artistic honesty; the writer defies convention, following his innermost desires and creative impulses.

Instead of being a debate between literary genres, the conflict between poetry and narrative—including the novel—is a debate between discourses. There is a well-known element of the story in poetry, and the novel, like Ghazi Al-Gosaibi’s novels, particularly *The Sparrow*, uses poetry as descriptive material.

Considering your book, Fear of Liberalism: Is Saudi liberalism distinct from the Broader Contexts of Gulf and Arab liberalism?

Firstly, neither the Arabian Peninsula nor the rest of the Arab world is a place where liberalism in the Western sense exists. Furthermore, liberalism as a whole in the Arab world is flawed as long as it confines people to religious interpretations and tribal procedures.

Secondly, our current manifestations of liberalism are merely formal and may reflect the beliefs of individuals rather than institutions and organisations.

Thirdly, I share this personal opinion: Why do we look for other people’s values to force them on our societies? It is preferable to draw from our social and religious values what is appropriate for the prevailing mindset to prevent conflicts between Arab societies’ elites and popular bases.

Politics works best when it strikes a balance and makes sense, not when it imposes the goals and ideologies of others. All of the Arab-imported projects, including the socialist ideologies that were popular in the 1950s and 1960s, have failed. These are only examples; concepts are uncommon because they differ from material inventions that can be applied under the material needs of societies and from the extensions of social thought.

How does Hassan Al-Nemi perceive the literary and cultural output of Gulf women in general and Saudi women in particular?

I disagree with the division of literature by gender. Regardless of the gender of the author, literature is fundamentally human. Literature is not intellectually valuable; it is purely aesthetic. Thus, literature consists of artistic formulas rather than the concepts we express. The majority of people who categorise literature as either male or female assume that women write about issues in their real lives, particularly those involving men.

Literature deviates from its literary essence to convey ideas according to this criterion. As a result, literature’s aesthetics—which are its most crucial component—are overlooked. “Means are simply laid out in the streets; ideas are of no importance unless they are cast in dazzling aesthetic moulds,” al-Jahiz once said, expressing the relationship between form and content.

Women’s writing has a problem because some of it has stopped at men. Although this has kept her from addressing more distant topics, it does not excuse her from claiming a privilege in her writing. The term feminism, which employs literature to defend women’s rights without consideration for literary beauty, is more complicated because there are authors who focus on women’s issues more thoroughly than the female writer herself.

The relationship that Arabs have with literature and culture is a modern conundrum and issue that tends to distance rather than to bring people together. What do you think? In your opinion, where is the issue?

At its classical level, literature is exclusive, but I don’t see any issues because understanding the nature of literature is one of the requirements for reception, and its metaphorical nature necessitates a mentality that can engage with it. Consequently, I do not believe that literature and Arab readers are estranged from one another.

From a critical scholarly standpoint, what is causing the gap between our Arab world’s intellectuals and politicians? Do we require an educational policy and political education?

Politicians are pragmatic and realistic, whereas intellectuals are idealistic and dreamy. A politician’s power is found in his choices, whereas an intellectual’s power is found in his words. A true intellectual should be a humanist who interprets contexts and uses his vision to express them, not a revolutionary.

Intellectuals who have witnessed all of the political changes in their nations and whose works have immortalised them abound. Despite living through both monarchy and revolution, Taha Hussein, for example, continued to be a writer and thinker who was unaffected by the ups and downs of politics.

Similarly, unlike nationalist and Marxist writers who elevated literature from its artistic and literary value to that of a political voice, Naguib Mahfouz, the writer who lived under monarchy and revolution, expressed them in an artistic way free from conflict. When the event ended, their creations died or their influence diminished.

What are the enduring and evolving aspects of Dr. Hassan Al-Nemi’s artistic and humanistic beliefs after a long career of creative and scholarly contributions?

Nothing stays the same, which is a constant. The law of life is change, and it starts with thoughts. If a person doesn’t change or grow, even though he is still alive, he is dead. Evolution is not the same as change.

Change has an effect on concepts and convictions, which is a shift from one state to another. Contrarily, evolution is advancement within the same framework without destroying it. In my literary, cultural, and intellectual capacities, I am a part of the evolving context.

Do you believe that the Arab world needs to improve its taste in literary and cultural interpretation? What’s the problem, and how can we fix it?

Taste and interpretation are not the same thing. In contrast to interpretation, which is production, taste is reception. When we receive a text, we might engage with it by savouring it. Interaction may lead the reader to an interpretation, which is a subsequent step, or we may simply enjoy it and stop there.

However, flaws are a relative problem that cannot be quantified. Depending on the texts’ nature and the reason for receiving them, every reception and interpretation experience is different.

Which major successes and failures, in your opinion, have emerged from the Kingdom’s nearly 100 years of narrative and short storytelling?

There are several benefits, chief among them being that narrative texts now account for as much, if not more, of Saudi literature than poetry in terms of perception and impact. The predominance of poetry at the beginning of the Saudi literary renaissance prevented the widespread use of narrative texts.

What literary and cultural pursuits does Dr. Hassan Al-Nemi currently have an interest in, and may he pursue them in the future?

Re-examining popular ideas in philosophy, literature, and thought has been a recent passion of mine. I believe that some concepts are unclear and skewed. As a result, I’ve made it the goal of my TikTok channel to discuss what I perceive to be some ambiguities in brief videos.

What viewpoint and method can unite the literary arts of the Arab and Gulf countries into a cohesive, integrated project?

They don’t have to coincide because literature is independent and influenced by its cultural background and influences. The fields of business and economics are more appropriate for projects that require planning than for the experiences of individual writers. Writers must, however, provide settings that improve their participation and presence.

Finally, how do you feel about Gulf societies’ literary and cultural fusion with their nations? Do you think that economic and political rivalry will prevent such integration?

As I have stated, literature, language, and culture transcend political and economic boundaries.

Diriyah’s Popular Cafés: Art & Creativity Collide with Genuine Heritage

Saudi Football Documentation Project: Extensive Disputation

Nammos Resort AMAALA: KSA’s New Address for International Luxury Hospitality

Muhammad Mahfouz: Trump will Respond to Riyadh’s Ambitions, and We Must Develop a Gulf-Arab Project with Iran

The World Stadiums & Arenas Summit 2025 has Arabisk London – Saudi Arabia as a Media Partner