Home » Business » What the Caesar Act means for Gulf states?

Business

What the Caesar Act means for Gulf states?

Published

2 years agoon

By

Huda

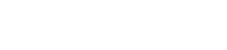

The Arab League’s decision to restore Syria’s membership in the pan-Arab organisation earlier this year marked a watershed moment in the rehabilitation of President Bashar al-Assad’s image at a regional level. In upcoming months, Syria’s renormalisation process is set to expand.

Among Arab statesmen, the trend is in favour of shoring up the Damascus government and supporting Syria’s reconstruction and redevelopment following 12 years of brutal war.

Yet, Western sanctions have, at least thus far, prevented the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and other Arab states from making significant investments in Syria.

The US’s Caesar Act, in particular, has cut off Syria from much of the international economy, largely due to its secondary sanctions that would target non-US-based entities should they do business in Syrian regime-controlled parts of the country. For example, soon after the Caesar Act came into effect the Lebanese company CSC Group stopped servicing Syrian ATMs.

Questions about Syria’s status will likely constitute some friction between Abu Dhabi and Riyadh, on one side, and Washington, on the other.

But it is worth asking questions about how much longer Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states that have reconciled with Assad’s government will continue being deterred from investing in Syria because of US pressure and sanctions threats.

Underscored by many high-profile visits to the UAE and Saudi Arabia in the past two years, team Biden values Washington’s partnerships with both GCC members and wants to avoid further aggravating tensions with Abu Dhabi and Riyadh.

The Biden White House, like previous US administrations, has relied on the UAE and Saudi Arabia in many ways. A recent example is the crisis in Sudan, where Saudi Arabia has attempted to mediate between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces while hosting US-supported talks in Jeddah.

The UAE also belongs to the so-called Quad, which pursues diplomatic efforts vis-à-vis Sudan in coordination with the United Nations.

Within this context, some experts doubt that the US leadership would impose sanctions on either the UAE or Saudi Arabia if these Gulf states were found guilty of violating the Caesar Act.

“The US might be politically apprehensive about this normalisation process but does not seem willing at this time to jeopardise its bilateral relationships with key Arab [partners] involved in the process, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE,” Dr Khalil E. Jahshan, the Executive Director of Arab Center Washington DC, told The New Arab.

He added that “US relations with these two countries, in particular, are too important for the Biden Administration to subjugate, at this critical time in the region, to the rigid application of the provisions of the Caesar Act”.

Other experts agree. “The Biden administration has not taken any meaningful steps to discourage Gulf partners from returning Assad to the Arab League,” said Gordon Gray, the former US ambassador to Tunisia, in a TNA interview.

“I do not see any appetite in the Biden administration for more robust engagement on Syria, so I doubt it has any real desire to impose sanctions on either Saudi Arabia or the UAE.”

Although the UAE and Saudi Arabia want to grow their networks in Syria while helping the country rebuild, neither Gulf power is necessarily interested in adding more friction to the relationship with the US if avoiding that outcome is possible.

“Abu Dhabi and Riyadh have openly declared their desire to exercise a measure of ‘strategic autonomy’ vis-à-vis the United States. At the same time, they are keen to maintain their close military cooperation with the US and to continue to remain under the American security umbrella,” said Dr Mehran Kamrava, a Professor of Government at Georgetown University Qatar, in a TNA interview.

“Therefore, whatever tactic they may adopt, they will be careful not to openly alienate or to antagonise the United States in the process.”

If necessary, the Emiratis and Saudis could use third parties as a conduit for investments, commercial activities, and business in Syria to avoid problems with Washington while the Caesar Act is in effect.

Putting money into Syria for humanitarian purposes and reconstruction could be done through NGOs and the United Nations. Abu Dhabi and Riyadh may also have some luck in terms of convincing Washington to make exemptions for GCC states that are putting money into Syria for humanitarian objectives.

Albeit with some level of risk and with limitations, it is worth considering how Gulf Arabs could invest in parts of Syria via Russia, Iran, or Turkey. “Some energy swaps associated with Russia or Turkey could be possible,” Rachel Ziemba, an Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security, told TNA. “There could also be some cooperation with Turkish construction and trade companies.”

Large-scale Emirati or Saudi investments in Syria could trigger Caesar Act sanctions, which punish firms and individuals in those Gulf countries, but not the UAE or Saudi governments.

“The risk of sanctions depends on the blatancy of the violation and whether the activity could be viewed as humanitarian. Arguably given the extensive restrictions on banking channels into Syria, any transactions remain very difficult, suggesting that any trade or support might need to take on the form of barter trade,” explained Ziemba.

“In practice, the UAE and Saudi Arabia may want to test the waters with arm’s length companies.”

The DC game and the influential pro-Israel lobby

Perhaps the UAE and Saudi Arabia could use their leverage in Washington to convince the US to soften its enforcement of the Caesar Act.

Within this context, one must realise that the UAE both joining the Abraham Accords and playing a major role in bringing other Arab states into the normalisation camp has given Abu Dhabi greater clout and manoeuvrability in Washington.

In the event that there is a push from elements within Washington to impose Caesar sanctions on the UAE, Abu Dhabi’s role in the normalisation process could help shield the Gulf Arab country.

“If indeed we get to a point where the United States threatens to impose sanctions on the UAE, which is an unlikely scenario, no doubt Abu Dhabi will resort to a variety of tools in its foreign policy toolbox, an important one of which now is its relations with the State of Israel and the pro-Israel lobby in the US,” said Kamrava.

“Both the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the UAE have extensive lobbying firms acting on their behalf in Washington,” explained Jahshan.

“Thus far, only the Emiratis have been active in limited lobbying on this issue. However, should their growing involvement in Syria generate serious opposition in Washington, particularly in Congress, one would expect the potential calls for sanctions against Saudi or UAE companies to require lobbying efforts to fight such [a] trend if and when it arises.”

The wider geopolitical picture

The UAE and Saudi Arabia’s relationships with the US have changed over the years. In a far more multipolar world, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are no longer taking orders from Washington.

They are increasingly determined to assert their autonomy from the West and pursue policies that the leaders of both countries believe serve Emirati and Saudi national interests. Bringing Syria back to the Arab League and welcoming Assad to Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Jeddah since March 2022 speaks to this point.

Aware of the leverage that the UAE and Saudi Arabia have over the US, officials in both Gulf Arab nations understand that the balance of power in their bilateral relationships with Washington is much more level than it was decades ago.

From OPEC Plus’s refusal to increase oil production to the UAE and Saudi Arabia’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are making it clear to the US that they are comfortable breaking with Washington’s foreign policy agendas when they believe that such policies are misguided or harmful to their national interests.

However, the Caesar Act has so far effectively deterred the Emiratis and Saudis to make major investments in Syria, which are in part meant to counter Iran’s influence in the country.

Perhaps this deterrence through the threat of sanctions will continue for a significant period of time. But there is good reason to consider the possibility of the UAE and Saudi Arabia finding ways to move around Western sanctions, if not flaunt them directly, at some future point.

At the end of the day, Assad and those in his inner circle know that neither Iran nor Russia has the financial resources nor the lobbying power in Washington to help ease Syria’s economic isolation as the Caesar Act continues choking the country’s battered economy.

This factor gives the deep-pocketed, US-backed Gulf Arab states unique cards to play when it comes to the situation in Syria and Washington’s approach to dealing with the reality of Assad’s government maintaining power and ruling over the majority of Syrian land and the country’s population.

Nammos Resort AMAALA: KSA’s New Address for International Luxury Hospitality

Muhammad Mahfouz: Trump will Respond to Riyadh’s Ambitions, and We Must Develop a Gulf-Arab Project with Iran

The World Stadiums & Arenas Summit 2025 has Arabisk London – Saudi Arabia as a Media Partner

Laheq: The First Private Saudi Island to Obtain Light at Last

The “New Square” Alters the Modern Life’s Notion in Riyadh